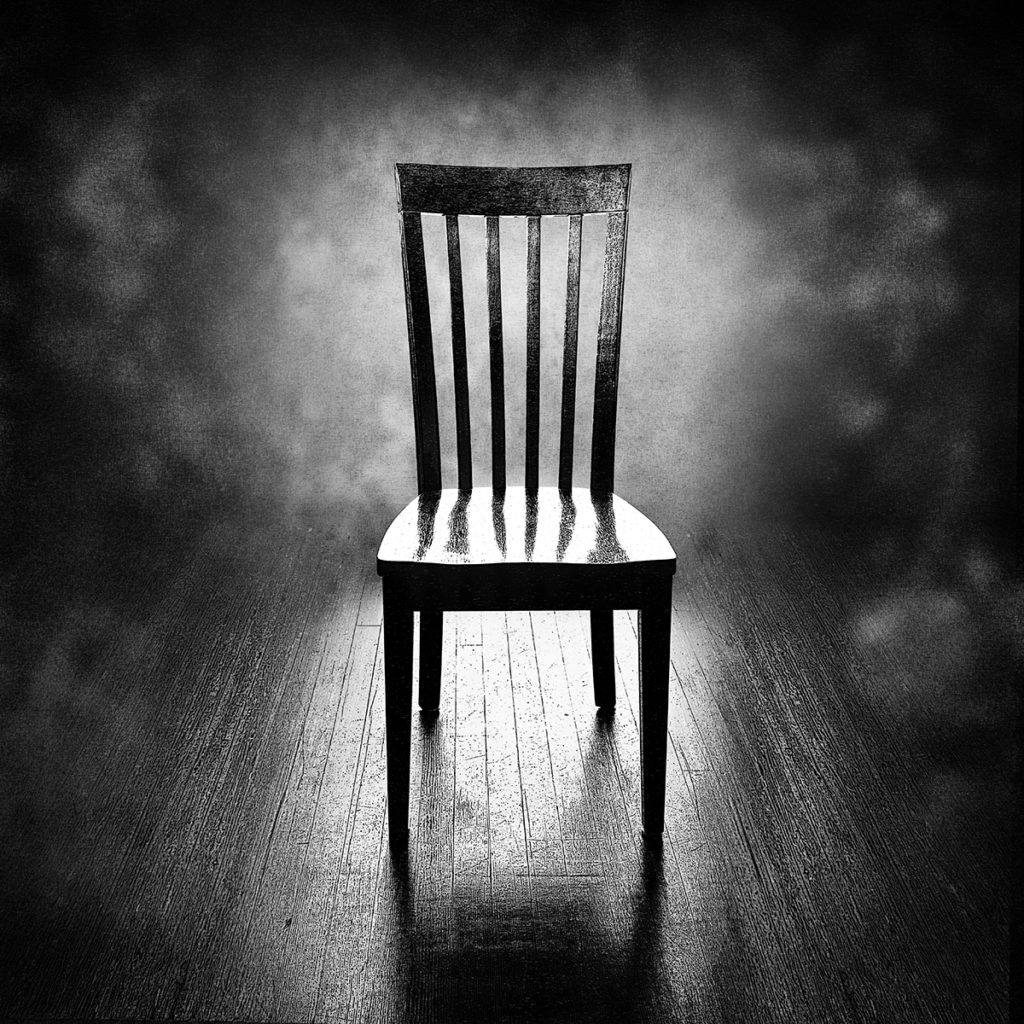

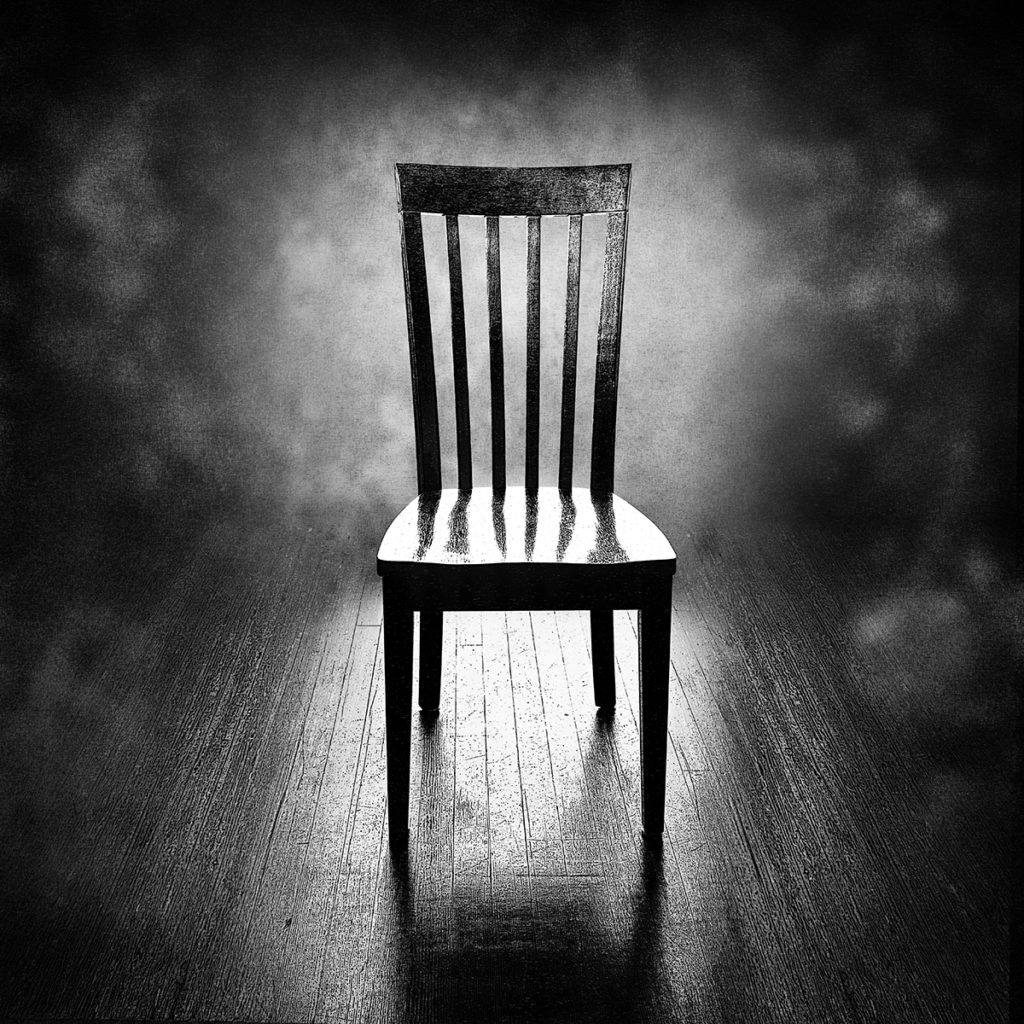

Day 791. I think. I wake in the cold damp of my room. My body crunched into a tiny almost-fetal ball. My cot is just barely five feet long. Long enough to lay on, but not long enough to stretch out fully unless I lie at a diagonal. First it’s the throbbing I notice. And then, it’s the bright, greenish white light piercing through my eyelids. Initially, it’s not the light that wakes me. Its the low grainy thrum. Grinding endlessly as long as the lights are on. A humming tonic of low metallic vibration. My tiny windowless room is about six by eight feet. Big enough for my child-sized cot, a stainless steal industrial toilet, and something that passes for a sink. Not much else. It’s lit with two very bright, mercury vapor high bays. The ceiling is tall enough that I probably couldn’t reach them if I were able. A fine wire mesh floats across, acting as a kind of false ceiling between me and the fixtures themselves. I can reach it if I stand on the bed, but the mesh is too fine to get a hand through. As I slowly begin to waken, to try to move, I notice where the ache is coming from. I’ve been grinding my teeth again. My molars feel dull and subdued. My jaw exhausted, the lactic acid from overworked muscles not yet flushed out. The inside of my right cheek is loose and wet and bloody, the consistency of mincemeat. I must have caught a tiny flap of skin between my teeth. I strain to open my eyes as I hear voices coming down the corridor.

The door to my room is heavy reinforced steel. The only possible breach in its design is the speakeasy. The opening is about ten inches square and has a metal sliding door only operable from the outside. Just inside of that, is a thick slab of clear acrylic. This allows the staff to look in without me being able to hear them or pass anything through. Normally they speak of me in third person as though I can’t hear them. They pass through the hallway in groups of twos or threes or fours. Often one white coat and the others in scrubs. Doctors, nurses, orderlies. I’m never sure. I sometimes think about trying to store up some really cruddy, concentrated piss to throw at them through the opening. But as of yet, I have not. As they come by this morning, they are only two. This time both in white coats. They rarely discuss medical topics. Usually its notes about my physical status. The cleanliness or smell of my room. The order of my few personal belongings.

Today I can only hear small parts of their conversation. “B2691 is one of our longest-residing guests,” I hear one of them say. I’m very rarely referred to by name. Usually it’s just B2691. Or sometimes 691. I know it must be Thursday today because I hear one say to the other “they’ll be brought down to the clinic for labs later today.” This meaning that I get a medical workup. Most of the time its just blood and urine. That takes place twice weekly. Monthly I get a full exam and every few months there is an even larger panel they run including endocrine response and marrow sampling. The few times I’ve had that, it’s been quite painful. I hope that’s not today. As they walk away, I notice they leave the speakeasy open. This almost never happens. I sit at the edge of the bed for a moment. Waiting. Waiting to see if another orderly will be by. Waiting to see if instead it will be someone else. One of the attending staff. Security. Possibly even Dr. Smith. I sit patiently. Nothing. No one. As I slowly stand to creep my way over to the door, the bed squeaks. The release of tension in the metal springs like a short, loud whine of a chamber door in an old house. I slowly make my way to the door. My breathe bated. My bare feet catlike and deliberate on the cold concrete floor. I peer forward to try to see out beyond my enclosure. I glance toward my left. Nothing. No one. As I begin to turn to my right, a hand reaches around with a small can of what looks like spray paint. Suddenly my eyes are filled with a thin smoke-like mist. It burns, and my nostrils are overcome with a sweet but slightly bitter smell. It creeps down my throat and as I stumble back toward my cot, my head goes light and I loose my ability to hold my body upright. I hear the speakeasy slam closed. Stumbling, I try to find my way to my cot to sit. I can’t quite make it. The floor feels gritty and dirty but pleasant on my bare skin. The cold smooth concrete is a slight relief on my burning cheek and forehead.

I begin to come to some time later. I’m not sure how long has passed. But I’m now seated in a wheel chair. My arms and legs strapped down. Even my chest is restrained. My vision is blurred and I feel my head throbbing. As the disoriented moments pass, I realize I’m still in the confines of my room. The door is open and I can see Dr. Smith and a younger woman also wearing a white coat in the hallway. She is plain. Caucasian. A slight build. Maybe late twenties or early thirties. Pretty, but nondescript. They’re looking over a document and discussing something I can’t quite hear. An orderly is adjusting the restraints on my ankles. Dr. Smith puts the papers back into the file folder as he sees me looking at them.

“Ah. 691. You are awake!” he says with some surprise in his exclamation. His voice is calm, smooth and despite the fact that I know him, has a modicum of reassurance. Under different circumstance, I might call his tone kind. He glances at his watch and then asks “how do you feel this morning?” I struggle to respond. I know he’s not really looking for an answer. My head still heavy. My vision still slightly foggy. I don’t yet have the energy it takes to form words. “Let me have a look at you” he says as he squats down before me. He begins to touch my arms, inspecting the skin, the feel of my muscles. He squeezes my upper arms and puts his hands on my shoulders. They rest there only a second before he cups my face in his palm. The way a mother might softly caress a child’s cheek. His touch feels warm and soothing. The astringent smell of soap wafts toward me. I start to nod off, but he lifts my head and forces open my left eyelid as he tips my head back. As I turn to avoid his stare and his intrusive prodding, he stops me. “No no no, look at me” he says sounding somewhat annoyed. With a small pinlight in his left hand, he holds the left side of my head with his free, right hand and lifts my lips to see my teeth and gums. “Do you know anything about the blood here?” he says as he looks up toward the orderly standing behind me. There is no response that I’m aware of. He prods further, pulling my jaw apart. With the small flashlight he looks in my mouth to see my torn up inner cheek and while probing at my teeth with a gloved finger asks “those bothering you?” With a reassuring smile he says “don’t worry. We can take those out. Your well-being is our number one concern.” The emotion leaves his face as he turns to the young clinician behind him and says “lets consider the removal of 14 and 15.”

Were I not in a half catatonic state, I might be even more alarmed. Later I will consider this and it will not be his tacit cruelty that will bother me most. It will be his icy indifference. Dr. Smith is a man singularly focused. He views me as a subject. Nothing more. There is no emotion that enters into his decisions with regard to my comfort. It is simply a matter of science. As if we are all just pieces in a game. Parts in a machine. As long as everyone does what they’re supposed to do, they system moves as designed. Emotion, be it feeling sorry for me, or me feeling anger toward him can only complicate the results. Dr. Smith does not like the idea of convoluted outcomes.

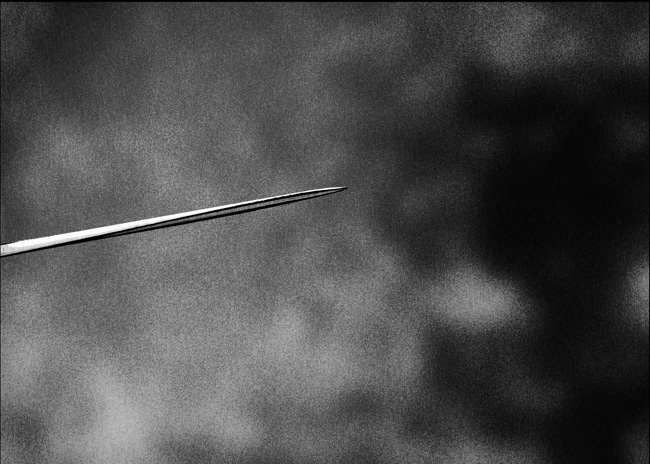

I see the clinician take a note. She stares at me. Deadpan. Almost as if she’s looking through me. Without curiosity or interest. I stare back at her. Dr. Smith removes his fingers from my mouth. As he stands, his body obstructs my view. His shapeless lab coat forms a blind that obscures my view of her, but a slight lean to her other foot allows her to continue to see me. In my periphery, I see her head peak above Dr. Smith’s shoulder. As Dr. Smith steps aside, I see her scribble more notes. I know she’s making note of the tooth extraction. I am too. But I’m trying to avoid thinking about it. I’ve never done teeth before. Hopefully they’ll at least give me anesthetic. Dr. Smith glances to the orderly behind me and just barks “lab” as he turns heel and leaves the room.

Beyond my room is a hallway. To the left, a dead end. There are a few rooms in that direction although many of the rooms in this corridor are empty. I’ve had only minimal interaction with the other captives. There was one a while back. Rammy was small. His big dark eyes always portrayed a sense of fear. In the dim light of the hallway it was impossible for me to see the space where iris ended and pupil began. I could occasionally hear him making noise down at the end of the corridor. But we rarely interacted. And then one day he was just gone. I asked Dr. Smith about him and was told the staff was here to take care of me and that other residents were not my concern. That was at least 300 days ago.

When I pressed Dr. Smith further, he informed me “The Center for Anomalous and Aberrant Biologic Studies has many guests. Many patients. They come and go in their own time. They are here to teach us about all the wonders that human biology, no matter how rare, has to offer us.” I wonder if he is aware that the they he’s referring to is me. I wonder if he recognizes his test subjects had lives before they came here. I wonder what a boy like Rammy, a child of only about twelve, would have to offer someone like Dr. Smith. I understand why I’m here. But did Rammy? Do the others? It’s hard to see this place as more than just a jail. Unless you’re Dr. Smith. And he seems to see it as anything but.

As I’m wheeled down the hallway, the orderly slows to a stop outside another room. The red metal door is closed tight against the frame, but the speakeasy has been left open. He glances quickly inside the room before shutting it. From the low vantage of the chair, I can see nothing. I hear nothing. I concentrate for a moment, closing my eyes. I try to listen with every cell in my body. Still nothing. We carry on to the gate. The first door is a large, reinforced glass portal. It is wide enough for a wheel chair or a gurney to easily pass through but it doesn’t quite stretch the entire width of the hallway. Out of the corner of my eye, I watch the orderly scan his badge and type his keycode. We pass inside the doorway. It is only after the door closes behind us that he can enter his keycode again to open the second, heavier, reinforced steel door. This door has a tiny window of mesh-lined glass, but is otherwise impenetrable. I notice the keycode is different on this side of the door than it was coming through the previous. Is the last digit variable? I’ll have to try to pay closer attention on my way back down. I’m so groggy still. These little details so difficult to commit to. All I really want right now is sleep.

Once we’re through the gate, I’m wheeled around a corner down another long hallway. This one is much like the others save for the paint scheme. There is no red here. The floor is a tiled vinyl of beige and brown. The walls a pale hospital green. It is long and dark and there are few doorways. As we pick up speed, the breeze feels soothing on my still-burning skin. I struggle to stay awake. I remember being a young child, in my mother’s car. Nodding off as soon as we got on the highway. This feels the same. The vibration under me lulling me to sleep.

After a very brief test set I am wheeled back to my room. Upon arrival at the gate, I am more alert. The orderly puts himself between the keypad and my view of it. I can only see around him slightly. I strain to see what he’s doing, trying not to move my body so much as to be obvious. I can’t let them notice that I’m looking. 1-3-2-1-3-4. I think.

Day 795. I wake much the same way I often do. My cold room bright and noisy. The lights ringing like tinnitus pounding. They come on automatically every morning at 7AM. They try to keep us on a controlled schedule. Dr. Smith always says a strict schedule produces the best internal rhythms. I feel less groggy today than I have been the last several. As I open my eyes and take in my surroundings, I stand. My bare feet meet with the cold of the floor. I shiver remembering how when I was a young child, I would get out of bed in the mornings warm and ready. My mother would always try to put a bathrobe on me. Especially in the winter, but I always threw it off. Now I think about what I wouldn’t give for a bathrobe. A sweater, another blanket. Anything to take this chill out of my bones. I sit back on my bed. My back near the wall, the stiff metal undercarriage supporting me. My legs crossed, I begin to go inward. I listen. First, I hear my breath. I try to hear what is beyond me. Beyond these walls. The plumbing and the electrical components. Beyond this building and the pathways and streets and infrastructure around it. To hear the water in the streams and the wind in the trees. Beyond the din of highway traffic to the particles in the air themselves. I imagine what it would be like to breathe fresh air again. To feel the sun on my skin. To feel a gentle breeze float across my bare arms. I imagine myself sitting on a beach. The sand soft and silk-like under me. The smell of salt and the sound of waves gently crashing just beyond my feet. Even with my eyes closed, I can see the sun and the clouds and the sky beyond.

Moments pass and I’ve settled into my own rhythm of breath. I come back to reality to the sound of yelling in the hallway. BREAKFAST 0-800. Just as I’m opening my eyes, I hear the speakeasy open. A face looks in at me, an orderly. A tall man with a scraggly beard. “B2691. I’ve been instructed to tell you that you wont receive breakfast today. Someone will be coming to take you to the lab shortly. Please stay seated where you are.”

Immediately, my internal peace is broken. I begin to wonder what it means that I won’t receive breakfast. Not that I ever really look forward to it. Sometimes it arrives still warm enough to put some heat into my body. But that is not what I’m thinking about now. I’m thinking that I know no breakfast can really only mean one thing. Anesthetic. Or some other drug. What will they do to me? Will it be just fluids they’re extracting? Blood? Urine? Spinal fluid? Or will it be something more involved? Like the teeth they alluded to the other day? Immediately I’m overcome with fear. Fear of pain. Fear of the loss of some part of me. Fear of how long it will take for my mind to clear after they’ve administered whatever pharmacological cocktail they’re testing on me today. And then I realize I’ve totally spun myself out. My heart rate is up. I’m no longer fixated on how cold I am. I’m not even really cold anymore. In fact I’m sweating a little. I take a deep breath. And then another. A sip of water. I try to calm myself. I close my eyes and remember the state I was in before the knock on my door. I remember the smell of the beach and the warmth of the sun on my body. I take another set of deep breaths. Just as I’m bringing myself back down, another knock on the door.

It is the sound of something dense clanking on the metal frame. Metal on metal. Like a full and weighty keychain. “691, please stay seated where you are” the orderly yells. As the door opens, there are two of them. The first, smaller, comes in pushing a wheel chair. The other much larger orderly is holding a baton. Why do they have to yell, I wonder. And what threat do I pose to them? Is it necessary for a 250 pound grown man to have to defend himself against a barely full grown body of 117 pounds with a police night stick? Have I ever given them reason to doubt my compliance? Its always seemed like a lot of defense and intimidation against a perceived threat that has never materialized. Sometimes I almost want to do something just to see what will happen to me.

I am ordered to come to the wheel chair and sit. I slowly do as I am told. I place my hands, as always, on the armrests and I am strapped in. Next my legs are restrained, then my chest. My breath is tight and constricted as I’m wheeled down the hall and into the lab. The orderly presents me to a clinician. The same woman from last week. I don’t know her name. As she comes toward me, she puts a mask over my face. “Just a little oxygen she says.” I look at her for a moment, measuring my response. “Is there not enough oxygen in the room?” I ask. “And I can’t really breath with this chest restraint on anyway. She looks at me quizzically before unfastening the belt around my torso. “Don’t you think this is a bit much”¦?” She looks at the orderly’s badge, then back at his face. “Don’t you think this is a bit much Johnson?”

“We’ve been instructed to use all restraints unless otherwise indicated ma’am” he says in a dismissive and unapologetic tone.

She does not acknowledge his response. Instead she turns back to me. “Just breathe slowly” she says. I feel myself nodding back to sleep.

When I wake, I’m back in my room. The hum of the lights like a freight train in my head. My brain aches. My mouth feels dry, like its full of cotton. I realize there is a large wad of gauze tucked between my cheek and gums on one side. Gagging, I spit it out. It is dry and bloody and sticks to my lips. A string of spittle drips from my lower lip, but the dry gauze wont release its hold on the inside of my cheek. My whole mouth is sore. My lips feel stretched out and dry; cracked. I make my way to the aluminum mirror above my toilet. As I peer inside my mouth, I can see in the dim light two of my upper molars are missing. I begin to obsessively run my tongue over the area of my cheek and gums. Even the touch of my tongue is painful. But I can’t stop. I wince every time the tip touches the edge of my gumline. But still, I am drawn to do it repeatedly. The taste is metallic. The edge where my teeth used to be is sharp, like a carved granite ledge. I’m unable to parse what I think my gum should look like and what it feels like. As I continue to peer into the reflection of my mouth, I am overcome with despair. How much more of this can I take? What is the point? How did I end up here? What am I not learning from this? I make my way back to my bed to lie down. My head and mouth feel hot, but the cold bedding chills my body. I wrap myself in the sheet, and lie motionless on my side. My legs curled against me. As I lie there, I try to focus on something other than the pounding discomfort. I try to feel every other thing in my body. The way my pants have bunched up around my calves. The way my blanket feels sandpapery on my bare arm and neck. The sound of the lights. I focus on every sensual element I can think of. I flit from one sensation to another. Some are tactile, others perceptual. I think I hear something in the hallway. I strain. But its nothing. Nothing I can grasp. Slowly, imperceptibly, I drift off.

When I wake, the lights are still on. I’m not sure how much time has passed. I cautiously roll to my back before sitting up. I sit for a moment, feeling both hungry and nauseated. The sour taste of blood still in my mouth. I resist the urge to tongue the chasm in the rear of my upper jaw. As I begin to regain consciousness of the room around me, I see the speakeasy open. An orderly peers in at me. “691? I have dinner for you. Please stay where you are.” I sit upright, my woolen blanket wrapped around me. Swaddled. The door opens, and the orderly places a tray on the floor. On it, a solitary cup and a pitcher filled with a dense, chalky-looking liquid. He backs out of the room with a slight smile and a nod, latching the door. Again, the speakeasy remains open. But today, this time, I have neither the energy nor the will to make my way to try to see out. I don’t even want to investigate my dinner yet. I remain seated for a while. I close my eyes, turn inward. It is all I can do.

As I sit, I listen. I can hear everything around me. The blood coursing through my body. In through my veins. Back out through my arteries. I notice the subtleties of how veins and arteries sound different. One constrictive, the other expansive. How I can feel the difference between a heartbeat in my feet and legs from a heartbeat in my chest or my head. I listen harder. Hearing what is beyond my body. Beyond my room. I can hear stirring in the hallway outside my door. Still I sit. Listening. I can hear beyond the walls of the building. I can hear the birds in the trees outside. The sparrows chirping and the chickadees flitting from branch to branch. I can hear dogs running through crunchy, dead autumnal leaves. A slight rustle of branches in the breeze brings me back as there is a knock on the door. I look up to see the Clinician’s face in the speakeasy.

“May I come in?”

I look at her for a long time trying to figure out if that is a serious question. She stares at me without expression. But I can see a hopeful expectation in her eyes.

“You have the keys don’t you?” I say. And before she can respond I ask “what if I said no?”

“You could say no.” She says cautiously, almost as if she were tiptoeing around my response. “But I hope you’ll allow me to talk to you for just a minute.” Her speech is measured. Its as if she pronounces each word deliberately and fully. The space between the words having almost as much importance as the words themselves. Her enunciation is bright-eyed and alert.

“Be my guest” I say without any physical gesture. I remain seated, my blanket still wrapped around my body. The idea of rushing her as soon as she opens the door crosses my mind. But it’s more like an idea or a thought experiment than anything with any motivation behind it. I’m still too tired to move. The anesthetic they’ve been giving me saps my energy. It can sometimes take days before I feel fully recovered.

The door opens slowly. As she steps in, she bends to pick up and move the tray still on the floor. Closing the door, she turns to me, tray still in hand and says “this was the first thing I wanted to talk to you about.”

She approaches me slowly. Cautiously. I remain on the bed, as before. She sets the tray down on the shelf opposite my bed. “We have you on a liquid diet for the next 24 hours or so” she begins. “If you have any problems with it, let me know and I’ll make sure they change it. Put you back on semi-solid food. Something else.” She pauses. “But its chocolate flavored. I bet you’ll love it.” She says it with such an optimistic lilt I almost grimace. It is the first time I’ve seen any emotion on her face.

I look at her with a vacant expression. I’d like my teeth back, I think to myself. Some nerve she has. She’s just pulled two of my molars merely to see what happens and she thinks I’m going to get excited about something that is chocolate flavored? It’s not even real chocolate.

“I’ve been reviewing your file” she says, returning to her previous, more cautious state. I’ve studied hundreds of case files for people with your gift. I wrote my graduate thesis on someone who had results like yours. He died 50 years ago. I haven’t come across anyone with so much promise since.” She pauses, looking at me. Waiting for my response. I say nothing. Emote nothing. “Do you understand how special that makes you?”

I glance around the room. Sterile white walls made of painted cinder blocks. A tiny little room with no windows. No access to fresh air. No access to fresh water. Not even a shower. The fact that I’ve done nothing wrong and that I put up with this without total unadulterated rage is what makes me special. I try not to let my thoughts color the expression on my face. I let my eyes return to meet her gaze.

“I know the situation must feel very isolating. Very confining” she says. “But I want to do whatever I can to make you more comfortable. To make this easier on you.”

I stifle a laugh. She looks at me somewhat hesitantly. I manage to play the noise off as something between cough and sneeze. This little noise is a mistake. The welling of friction in my throat is agony on my sore jaw. It feels like someone has shoved a ragged piece of sheetmetal into the gap in my gums and is twisting it. Gouging me with the rough edge. I wince in pain. I’m unable to conceal my discomfort. I take a breath and try to gather myself before looking back up at her. When our eyes meet she looks somewhat apologetic. “I’ll make sure they bring you something for the pain” she says. “I’ll be by to check on you in the morning.” She turns and walks away, stepping through the doorway. I can hear the click of wooden heels of her shoes as she scampers down the hall. I hear first the glass door open and close. I know she is in the airlock. And she is gone. And I am alone. I lay my head back down. To think. To feel. To try to reconcile where I am and who I am and what I want and what I need. I know what they want from me. But I don’t know if I can do it. Or even if I want to.

Up until now, its felt like the stakes have been low. The fingertip I know was a big display. And all the fingernails and the skin. That’s been easy. Or relatively easy. And it was the toes that got me into this mess I believe. But teeth? And two of them? How long will this take? Can I even do it?

Day 800. I wake to the sound of the thrumming lights as usual. The flagellate buzz of freeway traffic that is the ambiance of my room pounds on my head like an unwelcome visitor. As I come to consciousness, I realize my head is clear and I am feeling better today. The grogginess that comes with the anesthetic and the pain killers and whatever pharmaceutical amalgamation they put in my food seem to have run its course. More than that though, I just feel more alive. I’m not freezing cold. Maybe my request to the clinician yesterday that they make it slightly warmer in here did some good. Its just past 7 AM and I know the staff will be around with breakfast and morning meds and medical reports soon. I have about an hour before I’ll be forced to interact with anyone. I sit myself upright in the corner of the room. I nestle my back between the two walls sitting on the hardest, most reinforced part of my bed. The place where the metal styles and rails come together, still padded with the thin mattress. I cross my legs and with my blanket wrapped around my back, I close my eyes and turn inward. First I focus on my breath. I listen. I feel the air pass through my nose and into my lungs. I look to see what animation might play across the backs of my eyelids today. What Rorschach shapes will kaleidoscope through my field of view? Today, it is monochromatic. Mostly. A mix of reds, oranges and purples. I notice they move at the same pace as my pulse. A ratcheting motion like a water strider on a still pond’s surface. Each beat of my heart propelling it forth. It slowly slides to a stop before the next beat when it starts over again.

As I drop in further, a sense of my physicality first becomes visceral. I am aware of every muscle fiber. All the sinuous tissue that holds them together. Every skin cell forming anew and then dying. My hair follicles pushing slowly past the dermal surface. The feeling of my blood moving in to my right ventricle and out into my aorta. My oxygen-saturated hemoglobin passing through my pathways, slowly exhausting itself before returning to my lungs and starting over. But no sooner am I aware of my physical being, I am leaving it. Detached, I find myself surrounding my body. Not like I’m hovering over it or looking down on it. Nothing that hokey. Its more like I’ve grown larger than it. I encompass it. I am beyond it in scope, but not size. My head is light, airy, but alert. When I can attain this level of focus, it feels amazing. When I can’t, it can be a slog. Constantly drifting and returning. It can be Sisyphean. But it isn’t today.

I remember the first time it happened to me. I was in the wheel chair. It was about 2 days after the lawnmower accident. My foot was still bandaged and there was nothing really to see there except for the stump. Half of my big toe remaining, crushed and pulped resembling less a toe and more a rotten tree branch surrounded by meat. The other digits gone. The top of my foot chewed and gnarly like an old dog toy. I kept trying to make jokes about spoons that had fallen into the garbage disposal, but my mother would have none of it. All she could think about was how I’d be disfigured for the rest of my life. But after that second day, I wasn’t worried. Once I learned how to tap in, I could feel it come back. The pain was gone. And the skin came back quickly. I think it was on day 5 that my mother noticed. She was helping me change the bandage. And she could see most of my big toe had come back. The others were still tiny little stumps. Too imperceptible to notice. But at that point, there wasn’t even a reason to keep the foot bandaged. Other than it was still very hot and cold sensitive. I remember her saying “this is pretty gross kiddo. But its not as bad as I thought it would be.” She always called me kiddo.

After another week, the other toes had grown past the point of just being little stumps. They were still quite small. Tiny little piggies. But piggies just the same. My skin was still pink and raw and sensitive. And the nail beds looked like tiny little newborn mice. But where there had once been nothing, something was now afoot. It took about a month in total. The complete regeneration was not a fast process. But by the end of that month, I had a foot with five toes, all with toenails, and a good protective coat of skin. It wasn’t exactly good as new. But if you didn’t know I’d lost most of it, you’d never know it was ever missing. At that point I looked more like a burn victim or someone with a bad sunburn than a partial amputee.

The doctors were incredulous. They couldn’t believe it. At first they were ecstatic. But then they grew paranoid and suspicious. They accused my mother of giving me growth hormones and drugs. Unapproved drugs. Unlicensed drugs. Legal drugs, but in illegal doses. Anything they could think of that might have been the cause of something they were unable to explain. Was my recovery miraculous? Sure. Depending on your definition of miraculous. Was I a complete statistical anomaly? No. Definitely not. A rarity? Absolutely. The literature was there. They just had to look for it. But since they didn’t know about it, they resorted to explaining it the only way they knew how. I’m not exactly saying it was like the Salem witch trials or anything. But there was plenty of shaming and accusation. Enough aspersions were cast for there to be a serious case against my mother. And my well-being? That was never in question until the courts got involved. But all this is not important. At least not most of it. My story is about now. It is about me, sitting in a cold room with no windows, wrapped in a blanket for more than 2 years while I’m subject to a cat and mouse style game where parts of me are removed and I do my best to grow them back.

And that is where we are now. In my cold, poorly lit room. I’m swaddled in a blanket, sitting in the corner. I refocus my attention back to now. To where I sit. How it feels. The life of my organism. I send my focus to my mouth. Specifically my gums and missing teeth. For the next several weeks, or as long as it takes, this area will be the locus of my study. The pain and tingling and neurosis will be the target of my interest. The same as it was for my foot. And the finger tips. And every other thing that’s been taken from me.

Day 847. I wake in the dark. I’m not sure what time it is or how much of the predawn hours pass before the lights slowly hum to life. I find myself in the liminal state between sleep and wakefulness. This is the first time in months that I’ve been awake when the lights came on. In my early weeks here, plenty of nights lingered on almost eternally. The dark, silent ward echoing only its emptiness. It reminded me of the barred owls I used to hear in the spring time outside my bedroom window. Sometimes a pair would call back and forth. But other times, only one solitary member took the stage, a duet unfulfilled. It’s call going out, seeking a companion, but with no reply. The serenade noteworthy only for its absences. I felt like I’d just fallen to sleep when the hallway came to life. Without a clock, I can never be sure what time it is until the orderlies start making their rounds. The sounds of the ward are much like those of a springtime meadow. The crepuscular light giving way to dawn; the birds and insects snapping to attention. The sun calling them to action until the slow build of sound erupts in a crescendo of enterprise.

I slowly start to move and my cells flutter to increased action. I can feel my body temperature change and as alertness takes over from slumber, my pulse begins to quicken. I take a sip of water from the plastic cup beside my bed and bring myself to a seat. I begin my morning checklist, moving through the directory of sensation. I begin at my feet. At times, such as today, I can feel a bright tingle in my right foot; the one from the accident. Its somewhat like the tail of a newt. They can fling their tails off to distract a predator. The flailing, disembodied limb allows them a brief moment of distraction in which to escape. When the tail grows back however, its shorter, weaker and its ability to do the job of its predecessor is diminished. It still looks and functions like a tail. The newt can even throw it off one more time. But the regenerated tail is never as good as the original. That’s kind of how my foot is. Like my toes, my fingers are pretty good, but they too lack some of the gravitas of the ones I was born with.

Maybe the dexterity is something I will have to relearn. I’m lucky they chose only a pinky and wring finger on my non-dominant hand. Still, mild sensation persists sometimes. Its kind of an electrical buzz. Like getting stung by hundreds of tiny bees. Its sharp and itchy and a little bit painful but usually easy to ignore.

As I continue taking inventory of my body, I arrive at my head. I feel around in my mouth, using my tongue to probe the spaces between my teeth and along my gums. I notice my teeth feel like they’ve finally regrown completely. The skin around the roots does not feel exposed or raw anymore. The teeth themselves feel firm and solid. A week ago, they still had the undercalcified softness of a baby’s young bones. Today it seems the rejuvenation is complete. This observation brings me to another. In the past, when I’ve had to regenerate anything be it limb or flesh, I’ve had a period of exhaustion that immediately follows. I find myself lethargic and hungry and dehydrated. Its duration seems to depend on the length of the recovery period. I’ve also noticed that they seem to be growing longer as I am tested more and more. When I grew the toes back, it only took me a week or so to bounce back. But I was home, able to rest in the peace of my own bedroom. Under the care of my mother, like a baby bird under protective wing. Since I’ve been here, my intake and rest are somewhat restricted. Sleeping during the day though possible, is somewhat challenging. The lights never turn off, and neither does the noise of the corridor.

Day 853. I am running. Free! My bare feet come down in soft strikes in the cool, damp grass. I’m in the park again. The same one I sometimes go to with my mother. The sun is low on the horizon. The warm light casting long, hard shadows on the ground. Little insects buzz around in the clover under foot. The air is warm and balmy and it fills my lungs with each sweet breath. Although I’m wearing a hospital gown, I feel no sense of inhibition. I feel complete and utter joy. As I run and run the bits of cut wet grass stick to the undersides of my feet. The tiny dead blades lodging themselves between my toes. Ahead I see a young maple tree. Its leaves are green and tender and small. Its bark a warm, mottled gray. It is growing tall, but its trunk is barely six inches in diameter. I approach it as a speeding stock car approaches a turn. I pull wide and rocket myself around it nearly in the same direction I came from. This technique is also used by NASA to add speed or trajectory to an interspace object. The object approaches a planet and uses its gravitational pull to increase speed as it takes off in the opposite direction. I’m not sure the gravity of this small tree gives me any additional speed, but I feel weightless in my motion. The warm sun is shining hard on my face. I close my eyes to take it all in. I begin to feel the drawstrings at my back flapping open. I realize beneath my gown, I’m completely naked. The warm breeze sends a tiny shiver up my backside and I hear myself giggle uncontrollably; like a child.

I gallop on, the sun leading my way. Drawing me in, it is my homing signal. I can hear the frantic bark of a dog behind me. I open my eyes to see a puppy nipping at my ankles. Its soft black snout reaches and snaps, but finds no purchase as I pick up speed and pull away. It races faster to catch up with me. Barking, its clumsy stride is tempered by its oversize feet. I laugh harder and louder and I too begin to loose my breath. As I stumble into the soft green pillow of mossy grass, the puppy bounds on top of me. It is licking my face and I feel like even though I’ve never seen her before, we have known each other all our lives.

“What are you two doing over here?”

I hear the voice before I recognize its origin. The accent is unmistakable. Thicker than I remember it, but still, the words are clear. It is my mother. She’s standing over us, the dog and I. And she has a childish smirk on her face. “Are you having fun?” she asks as if she’s witnessing just another day in the park. Her accent is unlike any other I’ve ever known. She is South Asian, but grew up in Germany. She learned English as a child, but was never quite able to drop the tight Germanic corners or the sing-songy lilt of the sub-continent. I smile at her not quite able to speak. I’m still taking in her cavernous brown eyes and the somewhat puffy shape of her cheeks. I can’t believe its her. In a rush, I stand to hug her, so grateful to see her. But as I sit up and place my feet back on the ground, I’m overcome with the embarrassment of wearing only a hospital gown. Quickly I jump to my feet hoping she wont notice my naked ass blowing in the breeze.

“I’m sorry about my clothes,” I blurt out as I throw my arms around her. She hugs me back, but only for a moment and not with anywhere near the veracity I’m showing her.

“What are you talking about? This is the same costume you always wear” she says somewhat incredulously. As a child, I used to always laugh at her use of the word “˜costume’ when what I knew she meant was “˜outfit.’ “˜This is the costume you’re wearing for the first day of school?” she might ask. But today, it didn’t seem funny. It just seemed like one of those idiosyncratic things that made her my mother. And I loved her for it. As she pushed me back and looked at me again she asked “Are you feeling OK today Gulab?” And this time I did laugh a little. But not out of malice. Gulab was a pet name she had for me. Sometimes she used it in a serious tone, but always with reverence and fondness. I found myself stepping back a bit, somewhat overcome with emotion. Overcome to be seeing her, to have her in my embrace when I’ve missed her so much. But also with a level of confusion.

I look down to see my costume. She’s right. It is not the open gown I’d seen before. It is a t-shirt and a pair of simple cotton pants. What I always wore. I am still barefoot, but more so, I am confused. Had I imagined the whole thing with the gown? “Come” she said. “Lets go. You must be hungry by now.” As she takes me by my hand, a leash for the dog in the other she says “don’t forget your chapples” as she leads me away. My hand in hers, I don’t see any shoes of any kind. I just walk with her.

As we march through the grass toward the street, I realize we’ve been walking quite some time. The sun has dipped below the horizon and there is barely any light left in the sky. There are street lights I can see in the distance. The intermittent chirp of crickets rings through the evening air. I feel a chill on my skin, my bare arms especially, and my feet. They’re still wet and caked with grass. The air has grown cool and a damp fog is beginning to settle into the low grassy areas behind us. As we march along, I’m growing more and more tired. I turn to my mother to tell her I’m not feeling well when I realize she’s not there. The dog isn’t either. I feel a little lost. I decide I have to sit for a minute. As I approach the street, I can see cars parked around a cul-de-sac. I step off the sidewalk and sit on the curb. Feeling suddenly nauseous, I bend over putting my face between my knees. I close my eyes. I am cold and I wrap my arms around my legs and my torso, trying to give myself some body heat.

When I open my eyes and sit up, I realize I am in my room. Sitting on my bed, in the corner where I always sit. My blanket has fallen from my shoulders and my bare arms are covered in goosebumps; the gossamer hairs of my forearms standing at attention. As I pull the blanket back up around my myself, I look to my cold, bare feet. They are about as dirty as they always are. Not a trace of grass remains. Other than in my mind.

I sit for a moment, gathering my thoughts. As I contemplate my surroundings and where I have just been, I hear a knock and the sound of a latch. The speakeasy opens. I see the Clinician’s face. Respectfully, she announces she’s coming in. I stay seated in my corner. More alert today, I think about rushing her. She and I are probably about the same weight. At just over 110 pounds, I’m not exactly a force to be reckoned with. She is also of slight build, but she appears strong. Surprise would be the only advantage I would have over her. She comes in, closing the door behind her almost fully. I know there must be an orderly or someone else providing security just outside. I stay in my corner. Unmoved. But I take notice. I see the way she moves cautiously toward me. I see how the door remains every so slightly ajar. I could easily jam something in it, like my toothbrush to keep it from closing. They could still gas me. But with the door open, they’d have no way to contain it. I’m not saying I’m going to do it. I’m just thinking. Just making observations. Postulating.

I’m not a violent person. I never was, even as a child. I was never into video games or anything that was about war. I was a pretty docile kid. Sports, sure. I was a fairly good runner. Any game with a ball I excelled at, especially ones that involved dexterous running. As I got older, I had a harder time going against the bigger kids. Especially the boys. By high school, football was no longer an option. I could usually outrun and out maneuver the big guys, and even the more nimble girls. But getting tackled by someone who outweighed me by 100 pounds wasn’t much fun. So I avoided the more physical sports. Even soccer, which I was good at, was kind of tricky. I was too small to play with the boys most of the time and the girls didn’t really want me either. Unless it was a coed game, I was out. And then the lawnmower accident happened. I was almost 17 then.

As I said, I’m not a violent person. At least I didn’t used to be. Still now, I’m not. This place though, it makes me wonder. I have more violent thoughts now than I ever used to. And shouldn’t I? It’s not easy to be here, locked in a tiny room all day. I have limited time outside this room. Anyone would go crazy. Anyone would want to try to break free. And by whatever means are available. It’s not that I want to be violent. I just might have to make my escape. And if I do, I need to know what my options are.

“Good morning” The Clinician says as she gently pushes the door shut behind her. Her voice is somewhat chipper. There is more emotion in her tone than I’ve heard from her before. She even has a slight smile on her face. She glances quickly at the clipboard in her hand. “I have two things I want to discuss with you, but first, how are you today?” She does seem genuinely interested. At least as much as she has so far. But I’m still not sure if its a serious question or just some leftover social nicety. Perhaps something she learned in her residency in an old folks home. Either way, I’m surprised. I feign a slight smile but say nothing.

“Can I look at your teeth?” she asks as she pulls a small pen light from her coat pocket. Again, I’m not sure if this is a rhetorical question or not. But her bedside manner is better than Smith’s at least. He would have just forced my head back as he said “open.” So in light of that, I agree. And in doing so, I decide not to bite her fingers off. I open my mouth and tip my head back slightly so she can see. No point in being an asshole now. “Incredible” she whispers, mostly to herself. “Any pain or discomfort?”

Again, I wonder if that’s a serious question. She ripped two of my teeth out and she wants to know if I have any pain? How about “˜fuck you?’ How about I rip your teeth out and see if you have any pain? How about I just punch you in the face? I’m feeling mild-mannered today. One broken nose and we’ll call it even. I tip my head back down and close my mouth. We make eye contact as she steps back slightly. Her head is still only inches from mine. Closer than normal personal boundaries would typically allow. I stare at her, into her eyes just long enough to make her feel a little uncomfortable. She does not move. She just stares back. I notice all the lines on her face. The dark, bumpy skin that forms the light bags under her eyes. A thin line that spans the bridge of her nose. And the early crows feet. She’s too young to have major wrinkles yet. But I can see them forming. Crows feet. A funny name. But it suggests that at least she probably knows how to laugh. Something belied by her stern demeanor with me. Or maybe she just doesn’t own sunglasses. I continue to study her face. The boneless surfaces that make up her cheeks. White, smooth, like a snow-swept slope. I see her thin lips purse above her small, round chin. Again she asks calmly, inquisitively, as if breaking her own spell “pain or discomfort?”

“None” I say flatly. I continue to stare, but she steps back, breaking my gaze. She leans against the wall, opposite my bed. She makes a quick note on her clipboard and then looks back to me. I sit observing her, waiting for her to speak. I notice how uncomfortable she looks, bent at a slight angle, her feet sit about a foot from the wall, her lower back pressed firmly against it supporting her weight. Her upper body is leaned toward me as if she’s straining ever so slightly to hear what I’m about to say. I see the folds and wrinkles in her lab coat. The cascading waves leading from her hunched shoulders down toward her waist remind me of dunes made of the whitest, powdery sand. Because of the angle, only a small portion of the legs of her knicker length pants are visible below the hemline of her white coat. The periwinkle blue fabric falls, conforming loosely down toward her exposed ankles. I notice the way her bony ankles protrude and then retract back toward her heels. Her sockless feet sit firmly clad in black clogs, the toes pointed minimally inward toward each other.

It must be summer I think. I wonder if the sun is shining. I wonder if its warm and humid. Or maybe we’re having a cool snap and the humidity is low. Or perhaps its spring still and we’re having a spell of heat. I can almost hear the spring peepers in the nighttime air as I think about it. The damp smell of an evening thunderstorm just past. I catch myself thinking “˜we’ as if I’m among the free. Among the living breathing people, taking part in society and consuming the fresh oxygenated air that fills the empty vacuum of space that used to be known to me as “˜outside.’

“I’d like to start a new protocol with you” she says. “It will be a little more comprehensive than what you’ve been doing with Dr. Smith. Its going to require you to do more, but it will get you out of this room a little more too. There is a possibility, I can even get you some time outside. But as of right now, I can’t make any promises. We’ll have to prove to Dr. Smith my theory is working.” She pauses, looking at me, as if waiting for a response. “How does that sound to you?”

“OK” I say, somewhat suspiciously. “What does this new protocol entail?” And my first thought, is that it will be more painful. Yeah, I might get outside one time or two. But I’ll have to loose an eye or an ear to do it. I’m thinking this has to be some system of punishment and reward where I’m the one being punished, and she’s the one being rewarded. But I take a breath and remember that I can only deal with whatever is in front of me right now. And if that’s loosing an eye later, then I deal with it later. Right now, there are truths or inevitabilities that I’m not yet aware of. I can fear them, but without any information, I can’t plan for them. And that leaves me with fear alone which is not a productive use of the energy I have. I can gain nothing from it. It will only wear me down. And more than anything right now, I need my strength.

She went on to tell me that the protocol she planned would be more holistic than what I’d been doing with Dr Smith. To be clear, any “˜protocol’ I’d been on with Dr. Smith was more of a wait and see approach. He’d check my blood and urine a few times a week. And they mostly left me alone. Then he’d remove something and see what happened. He talked occasionally about establishing baselines and monitoring conditions. But mostly I felt like I stayed in my cell. I’d read or meditate or sleep when I could. But not much else. The Clinician on the other hand, wanted to reform all that. There would still be the rigorous routines of physical exam””the blood and urine tests and of course the more anecdotal exams””how I was feeling, etc. But she wanted to add in things she thought would stimulate me more. Foremost, exercise. She also wanted to improve my diet. Her thought was that if she could make me healthier, get me closer to living a life that was more similar to someone living in total freedom, the progress I’d shown might further improve.

So I agree. She tells me she’d like to start today. This afternoon. “We’ll start with a warmup” she says. “We already have a good baseline for you, but I think we can improve it. I’ll be back to bring you to the lab later today.” She says it with a slight smile. I find myself smiling back slightly. I feel a sense of optimism I haven’t felt in months. Maybe longer. The idea that perhaps she is my ally crosses my mind. That maybe I’ll have some human contact that doesn’t require me to be sedated or strapped into a gurney. I watch her turn and leave. She strides easily across the room and pounds on the back of the door with her open palm. The sound is hollow and cavernous as the metal door reverberates an echo through the room. “Coming out” she yells as she pulls the door open. She does not turn to meet my gaze. She just passes across the threshold. The door closes and latches shut. I hear the attendant’s keys turn the lock. And then there is nothing. No sound. Just the quiet of settling. The settling of silence. The settling of emotion. The settling of hope.

The meteoric rise in my mood is met quickly with its inverse. Like an emotional sine wave, my feelings seem parabolic. Immediately, I start to spin out. I’m overcome with anxiety. What if she wants me to trust her so that she can more easily hurt me? What if she doesn’t care if I trust her and I’m just falling victim to the fact that I’ve been stuck alone in this room without any real companionship for more than 2 years? I’ve been locked in here only allowed to leave the room when they take me either to the lab or for some godforsaken surgery. Of course she’s going to do something to me. That’s the whole point. That’s why I’m here. It doesn’t matter if I trust her or if she wants me to think she’s my friend. What she needs from me most is compliance. She has a job she’s doing here and I am her test subject. She holds all the cards in this relationship. My feelings are irrelevant.

I do my best to calm myself, but I am frustrated and angry and I can feel my blood pressure skyrocketing. I sit for a moment, thinking about what I know and what I feel. The two are not always dissimilar, but seldom are they the same. This is something I know about myself. I try to remind myself that I have a limited amount of control over my existence. That doesn’t mean my acquiescence to everything is mandatory. It just means that I can only worry about so much. Still, I find myself nervous. Maybe its because I have no idea what to expect. Maybe its because the idea that there is some hope that my situation will improve opens me to great disappointment. I ponder this for a moment. I ask what it means. What the ramifications are. Should it matter if I’m disappointed? Other then the obvious feeling of sadness, why does this idea bother me? If I have hope, can it only be met with disappointment? Or is there some alternative? Regardless of the alternative, should I give up hope and assume the worst? In what ways can that benefit me””emotionally or physically? I go around and around like this for some time. What seems like hours go by. Lunch is served and I’m still in my cell. Waiting. Anticipating her return.

Still more hours pass and I begin to think that I will not see The Clinician again today. But a knock comes at my door. The speakeasy opens. I see an orderly’s face. “691” he barks, almost yelling. As if I’m not only 8 feet away. I’m already looking at him. “Please stay seated, we’re coming in.” I hear the keys in the latch. The tumblers turn. The lock is released and the door slowly opens. The hinges creak, slowly grinding metal on metal against each other. The orderly steps in, a large man, he fills the doorway. His shaven head is stubbly like his face. His wide neck protrudes from his t-shirt like a tree trunk. His shoulders like buttresses. I know this man is immovable. Certainly by me. I can see The Clinician peering out from behind him. “Please stand and turn to face me please” he barks again. Is it me? Am I especially sensitive to sound? Or does he just think I’m hearing-impaired? I cautiously toe my way to the floor. I take one step toward him. Cautiously, then another. I stand, expectantly.

“We’re going upstairs” The Clinician says. In a normal tone and at normal volume, I note. The orderly approaches me. He has a set of shackles in his right hand. His large round keyring in his left. Seeing the long chains, especially in the hand of this giant man, I can’t help but feel a modicum of fear arise. I feel my heart begin to pound a little. As he steps toward me, I see The Clinician close the door. She stands in front of the open crack, blocking any passage. The orderly looks at me. We make firm eye contact before he speaks.

”Put these on” he says as he hands me the wrist cuffs. I look at him for a moment before I move. I take the cuffs from his outstretched hand. As I grab them, the long chain that connects the wrist and ankle cuffs drops to the floor making a loud clank as it collides with the concrete. I study the metal braces in my hand. They are heavy, stainless steel. Similar to a handcuff but instead of a simple chain between them is a heavy solid block of metal. A longer chain connects this to a pair of leg irons. As I linger, procrastinating putting the cuffs on, I notice the wear on the edge of the cuff. The metal plating has worn away here. Beneath the shine of the stainless steel is a warm, brassy sheen. The dull metal points my introspect to who might have worn these before me. What other hapless victim might have had the poor fortune of being forced to wear these? And for how long? How long does it take for finely polished steel to wear away? What abuse might this person have befallen? I run my finger around the pale worn edge.

“691, please put the cuffs on” the orderly barks. His tone is loud and jarring. I feel it internally, all throughout my organism. It inspires a bit of haste, even in me. I glance back up at him before I do as he says. I see The Clinician looking at me as well. Her face is not quite expressionless. But I’m having trouble reading what exactly she is thinking. I want her to feel shame. Or the hot flush of embarrassment. Or even anger at the injustice of what I know she knows I am subject to. But I remind myself that this is my view. Its my interpretation. Its what I want because I’ve already decided she’s supposed to feel like my ally. Like my friend. But she’s not. She’s just a clinician doing her job. And right now, her job is to take me to the lab. So I comply. I put the cuffs on. First the left, then the right. The smooth ratchet of the tabs pushing forth the spring in the lock mechanism. It is not as loud as I expect it to be. But the vibration pulses through my wrists. The bones feeling every tiny catch and release like a mallet. Like a tuning fork. Reverberating through my body. In slow motion. In sync with my fluttering heart.

Once both cuffs are on my wrists, the orderly steps forward to check them. To make sure they are tight enough. Too tight for me to escape. Too tight for me to have proper circulation. Too tight for me to momentarily forget I am captive. He bends down to put the leg irons on my ankles. One side at a time, he cinches down the cuff, locking the irons firmly in place around the hems of my pants. He gives them each a hefty tug. Its almost enough to tip my balance. The equilibrium of my tiny frame momentarily thrown off. He stands before me. Not quite looking at me. Looking mostly at the thoroughness of his handiwork. “Put your shoes on” he says firmly as he takes another step back. I do as I’m told, slipping the white canvas espadrilles over my bare feet. He turns and steps past The Clinician through the doorway.

I stand there for a moment, looking down. Looking at myself. Looking at these metal chains that constrain my slight, child-like body. I wonder what I did to deserve this. I wonder what horrible actions I could have taken in a previous life that would warrant such a punishment on my current incarnation. My current, adolescent life has been totally innocent. I cannot conceive that I’m being punished for anything I’ve done. I think about the camaraderie I now share with the thousands, no hundreds of thousands of people all over the world who are in bondage just the same as I am. Despite our guilt or the level thereof, do any of us deserve this? This loss of ability to take a single full step. To lift our hands all the way to our face just to scratch an itch. To bare the shame and humiliation that far outweighs the eight pounds of metal binding us inexplicably together. I feel a rush of anger come over me. I am suddenly incensed. I feel a slight sweat break out in my tight-fisted palms. As I clench my teeth, I look up to see The Clinician. She is looking at me. As I feel my heart rate accelerate and my blood pressure rise, I see a narrow in her gaze. She feigns a tight uncomfortable smile. It is not one that says “˜let me help you. Let me ameliorate this wrong. Let me seek justice on your behalf.’ It is instead, and quite obviously, one that says “˜let me do what I can to keep this situation under control. Let me do what I can to keep this quiet and orderly. Let me do what I can to keep this from getting any more uncomfortable for myself than it already has. Lets just get this over with for my own sake.’

We continue to look at each other a moment longer before she says a little bit too cheerfully “shall we go?”

I step toward her, the short length of my 24 inch inseam catches and snaps my leg back. I realize if I’m going to walk fast, if I’m going to walk at any reasonable pace at all, its going to have to be with short, hoppy strides. I slow myself. I take another step. And then another before I finally start to get used to the restrictive nature of my current situation. The Clinician steps aside, allowing me full access to the width of the doorway. I glare at her as I pass by. She steps through after me, and closes the door behind us. She puts her hand gently on the small of my back as we make our way down the corridor. With the orderly several paces behind us, still locking the door to my cell, she whispers “I’m sorry about the shackles. When I told them the wheelchair wouldn’t be necessary this was the alternative they gave me. I thought this would be a slight improvement.” She looks down at me. I can see the confusion on her face but I’m still too angry to allow her the pacification of letting her off the hook. “I’m sorry” She says again, this time more apologetically. I turn my face back to the hallway ahead. As we come to the double airlock door, the orderly has caught up to us.

Glancing back up at him, The Clinician says neutrally “everyone here?”

“Sorry” the orderly says somewhat automatically. He blurts it out in the way that men do. He’s not really sorry. It’s a phrase that social custom dictates. He says ‘sorry’ and what he means is “I realize you had to wait for me, but you, a woman and an inmate, don’t have any bearing on me or the pace at which I work.’ In reality, he’s not sorry. He doesn’t give a shit. If he felt anything at all, if he had any self-awareness, he would have said ‘thank you.” Instead, as he notices both of us looking at him he says “that lock gets a little sticky sometimes.” An excuse he makes in response to the acknowledgment that we know what he is thinking.

The Clinician reaches forward with her badge in her left hand and scans the code reader. After the tone, she enters her passcode with her right. I watch closely. 1-3-2-1-3-4. The door buzzes, and the orderly pulls it open. He holds the door for us. An act of implied chivalry. We step inside and as the door closes, The Clinician repeats the process. She scans her badge and enters her code. This time though, I notice it’s different. 2-1-3-4-5-5. That’s odd. I’ve noticed this discrepancy before. But I’ve never been able to put the pieces together. I don’t want them to notice me noticing them. So I quickly look away. I go back to clenching my teeth. But I try to think about this sequence. I think about what the two sets of numbers have in common. Logically I know that every door can’t have a different set of codes. The orderly Johnson here is barely smart enough to remember his own birthday. No less ten sets of codes for ten different doors. Even a person with average intelligence would have a hard time remembering that many six-digit codes. So I know there has to be an easy-to-remember pattern. Something that is somewhat intuitive or requires very little skill to figure out how the digits change from one side of the door to the other. I ponder this for a while. But I decide to store it away for later. When I have more time to concentrate without the stimulus around me.

We pass through the second door and stop in front of the elevator. As the doors open, we enter and The Clinician scans her badge again. This time, no code. She just presses the button for the floor. H. All the floors in this building have letters instead of numbers. I can only imagine its to confuse inmates in the event of an attempted escape. I don’t think I’ve been to level H before. As we exit the elevator, we make our way down another hallway. At the end of the hallway is a set of double metal doors. Much like those you’d find in a hospital or a school. No security is required to access them. They open freely. As we step through, we’re in another hallway. On one side is a bank of windows. I can see outside and the afternoon sun is streaming in. I slow my already stunted gate to spend a little longer taking it in. I can see trees and grass and a winding pathway that arcs wide around one wing of the building and the adjacent car park. Much like some of the other windows in this building, the glass is reinforced with a thin mesh wire. The mullions between the windows cast long, diagonal shadows across the floor. The wire breaks up the light just enough to give it the wavy appearance of water. Of light reflecting off a slow, easy undulation on a pond or a swimming pool. I can’t remember the last time I saw daylight. Its been weeks. Months probably. More than 100 days I’m sure. I slow even more, trying to take it all in. I take a deep breath as if I expect the cool spring air to rush into my lungs. It does not. But still my mood lightens immediately. I am lingering. Each step so short that my walk becomes more like a shuffle.

I feel The Clinician’s hand on the small of my back again. This time it doesn’t feel like she’s urging me on. It feels like she’s enjoying this moment with me. Her touch is soft. Almost tender. As I’m really beginning to take it all in, I hear the orderly’s heavy sigh. It’s so heavy, it’s as if he’s trying to push all the air out of his lungs at once. She turns to him. Quietly she asks “Do you have somewhere else to be Johnson?” He says nothing. He just stares at her. “I can take it from here if you have something else you need to be doing.”

“No ma’am” he says sheepishly, but mostly impatiently.

“Come on” she says. Her tone playful, but still firm enough to remind me that she has work she intends to do.

As we come to the end of the hallway, we pass through another set of double doors, again unlocked. To our left, we enter a room with the sign Physical Lab C on the door. Past this door, to the end of the corridor, I see a glowing green Exit sign above a door marked Stair. The room we enter has just a single metal door and only requires a simple badge swipe to gain entry. As we step inside, I see what looks like a physical therapist’s office at an olympic training center. There are rows of treadmills, stationary bikes, weight machines and other apparatuses of building physical strength. More than just the fitness equipment though are the computers and monitors and electronic components to measure and track a subject’s progress. I stand somewhat awestruck at all this. I’m not sure how to take it all in. Prior to now, all the testing I’ve done here has been through the removal of my blood, urine or other fluids. I had no idea anything like this existed in this facility.

Once inside, she brings me to a bench against a near wall. She asks Johnson to unlock my shackles. The orderly resists initially telling her that protocol states that an inmate be locked at all times. She explains that we are inside a room that cannot be exited without a security badge. But the orderly continues to resist. “I have you to protect me” she says sarcastically. The orderly finally complies, allowing me to walk freely. “Lets get you set up over here” she says pointing me to a treadmill in the middle of the room. “We’re just going to do a basic stress test today. This combined with your labs from yesterday will form our new baseline.”

She straps a heart rate monitor onto my chest and puts me on the machine. For 15 minutes I walk at various speeds and at various degrees of incline. Its all walking. Not stressful. But I feel so invigorated. Its the most movement I’ve had in my body the whole time I’ve been here. 853 days. More than 2 years. That’s how long it’s been since my legs walked at full stride. Or ran. Or my heart rate and respiration rates were elevated at the same time. And not out of fear or desperation or anger. But out of physical exertion, however mild.

My 15 minutes pass. They’re over in a flash. She tells me she has all the data she needs to start her program and that we’ll start in earnest tomorrow. She asks Johnson to put the shackles back on me and return me to my room. Something he is all too eager to do. On the return trip, I’m less incensed by the restraints. I still don’t like them. But I’m more enthralled by the endorphins that have been stirred in my crusty, cob-webbed brain.

Once back in my room I sit and contemplate my day. It would be easy to be swept away by the emotional whirlwind that has just passed. My meeting this morning with The Clinician. My time in shackles. My short stint on the treadmill. All of which brought their own set of stimuli far beyond my usual day to day here. Instead I try to focus on the tangible. I watched the orderly as he returned me to my cell. Through the airlock, his passcode was the same as The Clinician’s. The only difference was the order of the digits. What it looks like to me is a Fibonacci sequence. This is a basic mathematical sequence where each number is derived from the last two numbers before it added together. For example, the sequence I saw on the way upstairs earlier today was 1-3-2-1-3-4 on the way into the airlock and 2-1-3-4-5-5 on the way out. The difference here is that 1-3-2-1-3-4 is actually 13-21-34 not 3-4; 13 and 21 make 34. You simply add the last two numbers together to make the next number. In the example of the door code, its just a six digit sequence. Even the half-witted orderly Johnson can add 13 and 21. Knowing Dr. Smith, I’m surprised the security isn’t a little better. But I guess if you’re going to break out of this place, you still have to get past all the doors. All the beefy orderlies and then there are the cameras. Its not going to be easy.

The next day, Day 854, I wake as I normally do. The lights flicker to life. The loud irascible hum has yet to settle into a whining tonic. It takes a few minutes for the bulbs come up to full operating temperature. My day begins as usual. I wake. I meditate. I eat what they serve me for breakfast. Although today the breakfast patty and toast comes with a small salad. To see something green on my tray is quite a surprise. I’ve never eaten salad for breakfast before. But to see fresh spinach is a welcome surprise. This must be part of The Clinician’s new program. As promised, she comes to fetch me in the afternoon.

Much like yesterday, an orderly is with her. Not Johnson today. Today’s orderly is someone I do not know. He’s nearly as thick as Johnson, but a little gentler in his manner. He doesn’t yell at me and he’s a little less assertive with the tightness on the cuffs. The metal doesn’t dig into my skin and he doesn’t really treat me like a criminal. Although shackles don’t exactly scream innocence regardless of what saint might be wearing them. He and The Clinician take me to the Physical Lab again. She first takes a small blood sample and then she puts me on the treadmill. 30 full minutes today. “This is the new normal” she tells me. “Every day you’ll be in here. We’ll do blood most days and you’ll be on the treadmill most days. As you adapt, we’ll tax your physical capacity more. Up to a point at least. My goal is to give you a good diet and a little bit of exercise every day. I think it will help you.” I’m not exactly sure what she means by that, but I don’t ask any questions. I can only assume “˜help’ me means that it will be easier on my body the next time they remove part of it.

Day 947. I wake to the hum of the lights. As I always do. I am groggy and sleepy but I feel recharged for the first time in as long as I can remember. Although thinking about it, I realize I’ve been feeling pretty good in general lately. I’ve been clear-headed and alert all day. I haven’t felt the need for a nap most days. Even my meditations have been more focused. My sleep has been hard and restful. I’ve been mostly unable to remember my dreams. But the ones I do remember are vivid. And they usually involve my mother. More notably, there have been no surgeries or procedures of any kind since the teeth more than 3 months ago. I realize I feel more adjusted to my life here. I’m not saying I wouldn’t still leave at the first chance I got. But I feel like I’ve settled into a good rhythm. Something I can manage. Something a little more predictable. I understand that bondage is like water. It flows through me. Like a form of energy. It just has to be moved around. From one organ to the next. From bone to cartilage. From blood to connective tissue. This is the one respite I have. I recognize freedom is a concept. Not a place.

I also haven’t even seen Dr. Smith in weeks. I barely see him at all anymore. He is apparently more preoccupied with other inmates. I am The Clinician’s responsibility now. An adjustment I much prefer. She is generally kind to me. She and I have developed a bit of a relationship. Reluctantly, I’ve let her become my advocate. Perhaps she wants me to believe that she has my best interests in mind. It would certainly behoove her if she had my trust. But I have no reason to doubt her sincerity. Other than the teeth. Since then, she’s largely taken care of me. Still, I wonder sometimes if she really is prioritizing my well-being as she claims to. Or have all the little gifts: the food, the blanket, the change in temperature in my room, have they all been bribes?

Day 953. I wake just ahead of the lights. The only light I can see is through the clear, hard plexi of the speakeasy. Plus a little bit more from the hall spilling under the door. I know the lights are just about to come on because I can hear the buzz. They start to hum to life just before the bulbs do. Until the lights get warmed up, they’re dim and loud and blaring. It is a subdued version of a ship horn, the stern buzz warning everyone to abandon. Kind of a funny metaphor for the setting.

The Clinician comes in just after breakfast this morning. Much earlier than usual. She is quiet and furtive. More subdued than she usually is when I first see her. In the past month or more, she’s become much more bubbly. More emotive. More forthcoming. But today, she seems distressed. Before entering the room, she shuts the speakeasy. She closes the door behind her, almost completely. It doesn’t latch. But there is no gap in the threshold.

I am sitting on my bed. In my corner as I often am. I’ve finished my breakfast and am reading. Lately they’ve been giving me classic novels. I read The Catcher in the Rye when I was in high school. But I don’t have a lot of options. Its not exactly Amazon in here. So I’m reading it again. She comes close to me. She squats just below me. In a whisper she tells me they’re going to take a kidney. Just one–as if that’s a consolation. But she wanted to warn me. To tell me in private. She tells me she wants to talk to me more about it later today. But that we’ll have to find some place quiet. She says she’ll be by at the usual time to take me to the Lab. Until then I should go on with my day as normal. She promises we’ll talk about it more later. She turns and leaves. She does not look back at me. She also does not signal for security on her way out. She just steps through the door. This suggests no one knew she’d come to see me.

Immediately, I start to freak out. I try to keep it together, but I’m unable to control myself. I think about all that I’ve been through in the time I’ve been here. The last three months especially have been a big turning point. I start to cry. I sob uncontrollably as I consider what it means that I will soon be a victim of invasive surgery. All the other surgeries were less involved. The fingers were done under little more than local anesthetic. Same for the teeth. But an organ? This is serious. They are going to cut me open. Anything could happen. I don’t want this. I never wanted this. I ball my fists in rage and I slam them against my pillow. I hit it once. I’m not sure if it makes me feel better so I do it again. And again. I don’t know how many times I do it””six, maybe seven””before I snap back to reality. I am suddenly hyperconscious of my surroundings. Of myself. Of everything that I am and everything around me. I look to the door. The speakeasy is closed. But still I am cautious. I have to keep my composure. This is not a done deal yet. I tell myself to wait to see what The Clinician has to say about it before I really spin myself out. Obviously, I don’t have a good feeling about any of this. But I need to be patient. I need to keep my head. So I wipe the tears and snot and sweat from my face. I take a few deep breaths and I sit back in my corner. I try not to think. I try to just be present. To just feel. It has never been so difficult.

In the afternoon, The Clinician comes for me as she usually does. When she arrives, she is stone-faced. She looks pale. I’m still upset, but I feel like I’ve pulled myself back together since this morning when she first told me. An orderly is with her and with shackles, they collect me as normal. There is not much talking today. They announce their entry and the orderly hands me the cuffs. I comply without resistance and we go. All of us quiet. Its as if we’re trying to conserve what little oxygen we know is quickly fading from the room.

When we arrive in the Physical Lab, she puts me on the treadmill. She seems preoccupied and unfocused. All of her motions are rote. She does not ask me how I feel today or if there are any changes in my physical or emotional state. She just hands me the chest strap for the heart rate monitor and points me in the direction of the treadmill. Usually she turns it on and sets the pace for me. Today, she does not.

It’s not uncommon for the orderlies to leave for a few minutes once things get moving in the lab. Usually they go to the bathroom or to have a smoke or something. They’re never gone long, but I always notice when they duck out. Today is no exception. As soon as we’re alone, The Clinician comes close to me. She stands next to me. She starts speaking in a low tone. I can barely hear her over the whirring belt of the machine. I reduce the speed so I can better hear, but she turns it back up. I am almost running. Trying to stay focused, I look back and forth between her face, and the wall I am facing. I am trying to hear her and not fall. The pounding of my feet on the surface is distracting. My heart rate is up and it is a challenge to understand everything she’s telling me.

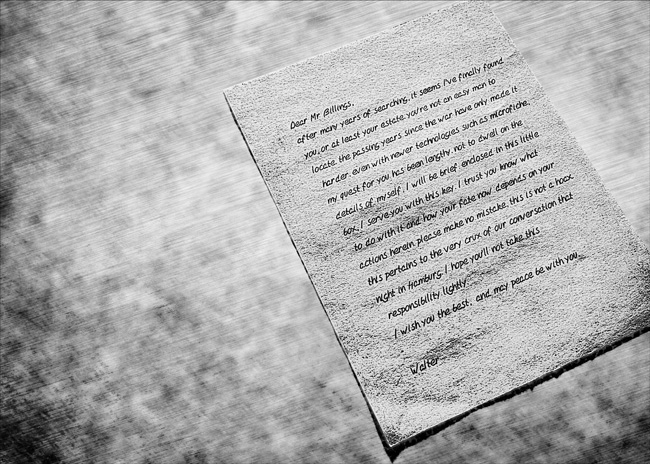

She starts by saying that Dr. Smith wants to take a kidney. This she told me this morning. Its not news. I’m unfazed. It is Tuesday today, she tells me they’re planning to do the procedure on Friday. She tells me she feels horrible and that she’s contemplating helping me escape. She starts babbling on. I can’t exactly hear her. Something about how she feels conflicted. How she wants to help me but she’s not sure how. At this point, I start to zone out. I don’t say much. All I can think about is how they’re going to remove one of my kidneys and she’s made this about her. Sure she feels bad. Like she’s complicit. But she’s been complicit this whole time. This is not new.